‘The Godfather of the Jordan Brand’: How Howard White found his calling as Michael Jordan’s closest confidant

By Aaron Dodson

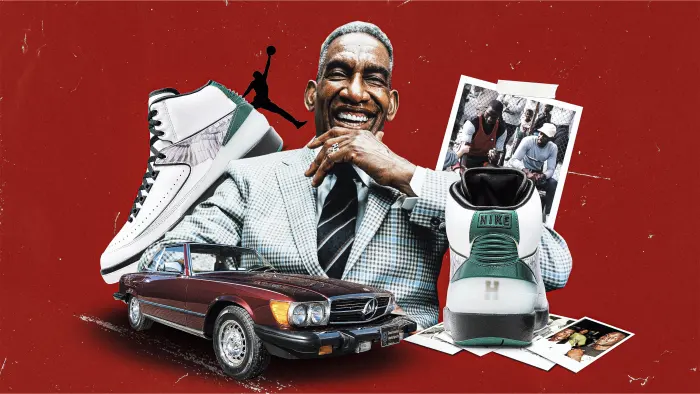

A movie character, a Mercedes-Benz and a heart transplant — the many stories behind Nike’s longest-tenured Black executive, who helped build Air Jordan

There’s only one person who’s been alongside Michael Jordan for the entire story of Air Jordan.

Howard White, the smoothest of talkers, has been the man behind the scenes for Jordan and his brand since the beginning.

Back in 1984, White — who’s now 72 and the longest-tenured African-American executive in Nike history — sat in the room during the company’s original pitch to Jordan and his parents. Later that year, when Jordan signed an endorsement deal with Nike that changed the footwear industry, he became Jordan’s daily manager and mentor.

White witnessed Jordan win six NBA championships in his signature sneakers. And by the end of Jordan’s tenure with the Chicago Bulls, he persuaded Nike founder Phil Knight that Air Jordan — and the Jumpman logo he inspired — could keep going.

The vision White helped craft resulted in the launch of the Jordan Brand in 1997. Today, it’s a $5 billion subdivision of Nike, and White has been its vice president for the past 25 years.

“The heart and soul of Nike and Jordan?” White asked Andscape via Zoom from his Lake Oswego, Oregon, home. “I’m not sure I’m those things, and I’m not sure how it all happened. I’ve just kind of been me.”

This week, he’ll receive flowers in the form of a sneaker, with the release of a limited-edition Air Jordan 2 “H” Wings on Saturday, honoring his legacy with the brand.

Yet sometime last year, Jordan delivered a personal testament about White’s role in his story after actor/director Ben Affleck approached him with the idea of a feature film depicting the genesis of Air Jordan.

“Howard White needs to be in the movie,” Jordan explicitly told Affleck, who cast actor Chris Tucker as the young executive in Air: Courting A Legend.

“Howard doesn’t carry himself like it, but he really is the Godfather of the Jordan Brand,” Tucker told Andscape before Air’s April 5 release. “I didn’t want to let him down.”

These are just some of the countless tales surrounding the man who Jordan and everyone else simply calls “H.”

Inside the boardroom where Nike pitched Jordan in 1984 sat a dream team of footwear executives — the brand’s director of marketing Rob Strasser, creative director/footwear designer Peter Moore, marketing guru Sonny Vaccaro, and, of course, White. At the time, he was working as Nike’s NBA promo man.

White was the only other Black person in the presentation outside the Jordan family. So, he’s had Jordan’s attention from day one.

“H has always told me,” said Reggie Saunders, the Jordan Brand’s current vice president of entertainment marketing. “ ‘This Jordan thing is a dream. And it’s a damn good dream we’re living.’ ”

“I don’t do much,” Jordan told USA Today in 1998, “without at least talking to Howard White.”

Hall of Famer and former Nike signature athlete Charles Barkley once called White the sole angel on his shoulder during his NBA career. Pro Football Hall of Fame cornerback Deion Sanders swore by White, too.

“He makes you feel like a person, not just a prostitute for a company,” Sanders, another former Nike signature athlete, said in 1998. “H is the glue that keeps players at Nike.”

That’s because White talks a talk that can resonate with anyone who will take the time to listen.

“This is a guy who was Michael’s first marketing rep at Nike,” said Saunders, whom White hired in 2007 to expand the Jordan Brand’s reach into entertainment. “So, of course, you bring H into meetings because you want people to hear the lineage of the Jordan Brand — how we were built, why we were built this way, and why we’re the best. H has a reason for every single thing.”

White is the ultimate pitchman, and it’s tough to tally exactly how many presentations to athletes or celebrities he’s sat in over the years. Just know that in the past 4½ decades, if Nike or Jordan really wanted someone to endorse its products, White has received a call, email or Calendar invite.

“When Jordan signed Drake, H was in the meeting,” Saunders said. “Travis Scott always wants to see him, ‘How’s H.? Where’s he at?’ DJ Khaled loves H, too. And Fat Joe, who’s a big personality himself, always grabs him when they talk. Jadakiss even sat in H’s office one time for maybe two or three hours, just talking.”

Ten-time NBA All-Star Carmelo Anthony fondly remembers meeting the man who helped bring Jordan to Nike — and eventually him — to the Jordan Brand as a rookie in 2003. The unforgettable exchange between Anthony and White unfolded at the first Jordan Brand Classic in Washington when Anthony was 17 years old.

“H had this godfather aura,” Anthony told Andscape via email. “He just has this confidence about him. Being young, it was cool to see this Black man move.”

While the Jordan Brand courted Anthony, White also played a vital part in assuring that Nike landed LeBron James, the 2003 NBA draft’s eventual No. 1 overall pick by the Cleveland Cavaliers. White dialed Aaron Goodwin, James’ rookie agent, minutes after the then-18-year-old James met with Reebok the night before the May 2003 draft lottery.

On that call, detailed in the 2007 book The Franchise: LeBron James and the Remaking of the Cleveland Cavaliers, White passed along a simple message from Nike’s boss. White told Goodwin that Knight — more than anyone — wanted James at Nike. And more importantly, as White extrapolated, that meant Knight wanted a deal finalized ASAP.

A few hours later, James ended his sneaker sweepstakes by joining Nike in the richest rookie shoe deal ever signed by a basketball player. So, in 2003, Nike and the Jordan Brand landed two of the NBA’s top-three draft picks in James and Anthony, who was selected No. 3 overall by the Denver Nuggets.

“H is like a B-52 stealth bomber,” Saunders said. “He’ll chime in when you need him and, you already know, he’s coming in hot.”

Phoenix Suns point guard and 12-time All-Star Chris Paul first heard about White while playing at Wake Forest University, where one of White’s nieces was a classmate. True to the godfather vibe he gave Anthony, White immediately impressed Paul with his custom suits, patterned ties and white pocket squares.

“Every time I’d see H. White, he’d be suited and booted. Always dressed and pressed,” Paul told Andscape. “He’s the slickest-talking person you’ll ever meet in life. And I’m grateful for him. I know my career with Brand Jordan wouldn’t be what it is without him.”

Other than Jordan himself, no players have received more Jordan signature sneakers than Anthony (13) and Paul (12).

“I’ll also say this,” Anthony added. “Whenever H steps into a room, he has a story to tell. And it’s always a great one.”

If there’s a single anecdote White revisits most, it’s the memory of a Saturday stroll down Calhoun Street with his mother, Lillian.

White grew up in Hampton, Virginia, in the 1950s. And when he was about 9 or 10 — around the time the city’s public schools were desegregated in 1959 — Lillian took her son into town with her to run some errands. That morning, they passed an ailing man in the neighborhood named Mr. Lee.

“Hi, Lee, how you doing today?” Lillian asked.

“How you doing, Ms. Lil?” Lee, who walked with a limp, responded. “You have a good day, you hear?”

Young Howard, though, was distracted. Rocks in hand, he was fixated on the stop sign at the end of the block. “I was thinking if I could hit the O right dead in the middle,” White recalled, “the cow would jump over the moon and the stars would run around the sky.”

That day, Lillian White stopped, grabbed him and spoke sternly.

“You let that be the last time,” Lillian told her son, slowing her cadence to assure he heard, “in your life that you ever walk by someone and not open your mouth to speak.”

The 15-word parable she delivered next has been ingrained in White ever since: “Because even a dog can wag its tail when it passes you on the street.”

“For whatever reason,” White said now, “that day, I became who I would become.”

He now speaks to everybody — young or old, Black or white, CEO or custodian, the greatest of all time or last player on the bench — just like his mama once told him to do.

To support her six children, Lillian White worked as a maid for a white family who owned a Hampton marina. That was life for a single Black mother in the South, still experiencing more than 70 years of Jim Crow.

“Before there was any business experience at all, there was a set of values instilled in him by his mother,” Knight penned in the foreword of White’s 2003 self-help book, Believe to Achieve: See the Invisible, Do the Impossible. It’s the same name as a leadership program White established at Nike in the late 1990s. White also played a vital part in the 2015 launch of the Jordan Brand Wings Scholars Program, which awards full college scholarships to underprivileged high school students. Each year, the brand drops a sneaker to support the initiative, and this year, the Air Jordan 2 “H” Wings pays tribute to the Wings co-founder.

For White, Lillian remains the inspiration behind what’s one of his most noticeable traits. Whenever he’s asked about a specific Nike or Jordan Brand athlete, past or current, the first thing he’ll offer is a fact, story about or, most admirably, the name of the athlete’s mother. White has made a career by signing mama’s boys, like Jordan and himself, to endorsement deals.

Of course, there’s no athlete’s mother White is tighter with than Deloris Jordan, or “Mama J,” as he affectionately calls her. Every major holiday, from Easter to Mother’s Day and Christmas, he picks up the phone and calls Mama J.

White also occasionally mentions two Marys — mothers of the same name who raised both Anthony and Hall of Famer Moses Malone, who became the first NBA star White worked with at Nike in the late 1970s. White loved Barkley’s mother, Charcey, and grandmother, Johnnie Mae, so much that he delivered eulogies at their funerals.

“Howard started at Nike just trying to keep young kids, like Michael was at the time, away from trouble. He tried to just be that third eye for Michael,” Tucker said. “That model went on to Charles Barkley, to Tiger Woods, and a lot of different athletes in Nike’s stable.”

As detailed in a 1997 Augusta Chronicle story, golfer Tiger Woods’ mother Kultida walked all 18 holes during the Saturday round at The Masters in 1997 with White by her side.

Nike had signed Tiger to a five-year, $40 million endorsement deal in 1996. And by the 1997 Masters, the brand’s big investment became the youngest golfer at age 21, and the first man of Black or Asian descent to win a green jacket at the PGA’s most-coveted major.

Woods’ father Earl and Knight watched from the clubhouse as Woods put on a four-round master class that he completed with a 12-stroke margin of victory that still stands as a tournament record.

Meanwhile, White, wearing a white Nike beret under the Georgia sun, escorted Kultida Woods around Augusta National until she was ready to return to Woods in the clubhouse following his round.

The story of how White became known as “H” could be the pilot episode of his life’s miniseries.

Back in the 1950s and 1960s, a wooded area divided the side of Hampton where White and his family moved to live with his mother’s sister Hattie after his father left.

Integration had been embraced on one side of the woods — the safe side. Black folks in Hampton had cultivated a local legend about the other side, similar to other tales of “sundown towns” the South was known for. As the story goes, a sign there read: If you’re here when the sun goes down, you won’t see it come up. Though White said he never actually saw the eerie warning, he swears on everything the sign stood.

One afternoon, White and two of his friends, Herman “Terry” Prescott, and Carlton May, rode their bicycles to the infamous side of the woods, where a new school had been built. The integrated Kecoughtan (pronounced KICK-a-tan) High opened in 1962 to support the overflow of students from the county’s largest secondary school, Hampton High.

White and his boys walked into what initially appeared to be an empty basketball gym. Then, they noticed three white men on the other end of the court.

“I’m like, ‘We gotta get outta here. We don’t belong here,’ ” White remembered. “But, as we’re leaving, one of the men said, ‘Hey! Y’all wanna play a game?’ ” The man tossed over a basketball to the three Black boys.

“It was a whole game of, ‘No, son, you gotta check the ball. No, son, you gotta take the ball behind the line,’ ” recalled White, visibly growing irked by the memory. “The whole damn game was ‘No, son, the ball gotta go somewhere else!’ They beat us to death.”

Right before the boys left, one of the men interrupted White as he drank from the water fountain. The man introduced himself as Jim Hathaway, the basketball coach at Kecoughtan. Hathaway asked White, then in junior high, one question: Have you ever heard of “The Big O”?

“Of course, I know the Big O!” White responded. During his childhood, NBA point guard Oscar Robertson was a household name. “That was like asking somebody now if they ever heard of Michael Jordan, LeBron James or Kobe Bryant.

“But then,” White continued, “Coach Hathaway said something even dumber.”

He guaranteed White that he could coach him into a player, maybe not of Robertson’s caliber, but pretty close.

“I figured if he was stupid enough to believe it, then I could be dumb enough to listen,” White said. “Coach Hathaway taught me how to shoot. He taught me how to dribble. He taught me the entire game of basketball.”

Under Hathaway’s tutelage, White became an All-American point guard at Kecoughtan.

“One of my dad’s old school friends always tells the story of Coach Hathaway specifically being told, ‘Don’t start a Black kid. Nobody will come to the games,’ ” said Mandy White, the 34-year-old daughter and only child of White and his wife. “In actuality, the line would be wrapped around the whole building to come see my dad play.”

According to a 1969 story by the Daily Press in Newport News, Virginia, more than 200 Division 1 college basketball programs recruited White.

Offers stood even after coaches discovered White had a “gimpy knee,” as The Press called it, that he injured during his senior season. At 18, White underwent his first knee surgery. Afterward, as he remembers, the operating physician told his mother, “His basketball days are over.” But he couldn’t let go of his hoop dreams. White narrowed his college decision to four Division 1 programs: Kansas University and Maryland, North Carolina and Virginia.

“He’s by far the best guard in the country,” Maryland coach Lefty Driesell told The Daily Press. “I’m just praying he elects to come to Maryland.”

The highly touted point guard’s recruitment ended with his commitment to play for Driesell and the Terrapins. And because of White’s knack for persuasion, the back of his Maryland jersey throughout his four-year college career simply read “H” in quotation marks over his No. 13.

White emerged as “The Big O” of college basketball, fulfilling the promise Hathaway put into the universe the day that he and his friends walked into the gym for the first time at Kecoughtan High School. (In late 2021, the street leading up to the gym was renamed “Howard White Way.” Inside the gym, White’s No. 13 Warriors jersey hangs in the rafters over the hardwood floor, named “Howard White Court.” The Jordan Brand also sponsors the athletic programs at Kecoughtan, where the Howard White Classic basketball tournament is held annually.)

Yet by his senior year at Maryland, White sustained another injury, this time to his other knee, which required more surgery.

White relinquished his job as Maryland’s starting point guard to a “young man from Durham, North Carolina” named John Lucas. Yet even with knowledge of his history of nagging knee injuries, the Capital Bullets selected White with the 192nd overall pick in the 14th round of the 1973 NBA draft. That’s right: White reached the NBA. But, unlike at the end of high school, he accepted that his knees couldn’t take him any further. White decided his playing career was finally over.

“I figured although I was a great basketball player, somebody in the world must not have wanted me to play basketball,” White said. “Or else I wouldn’t have kept getting hurt. So, I thought there must’ve been a greater calling for me, as crazy as that might’ve seemed then.”

For a few years, White remained in College Park, Maryland, after Driesell created a position for him as an assistant coach on his staff and the university’s assistant director of intramural sports. The legendary Lefty knew he had the ultimate recruiting weapon in White’s sweet-sounding voice. So, he deployed him on the recruiting trail. White’s first mission: Secure a commitment from a 6-foot-10 center from Petersburg, Virginia, named Moses Malone.

“Mo was the best player I’d ever seen,” said White, who can still rattle off Malone’s remarkable averages of 35 points, 23 rebounds and 12 blocks at Petersburg High School.

The first time White drove from Maryland, down Interstate 95, to visit young Moses, his mother answered the door of their two-bedroom rowhouse. Mary Hudgins Malone, a single Black mother like Lillian White, told White her only child wasn’t home. The respectful recruiter asked if he could still come inside and wait for the high school star everyone wanted. A run-down Mary Malone obliged, fresh off finishing a long shift at her $100-a-week job as a supermarket meat packer. White sat on the couch, and Mary Malone turned on the TV. They watched soap operas together until both dozed off. That afternoon, White earned the trust of the woman who had raised the best prep player in the nation on her own.

“She said, ‘I’m gonna tell ‘Tiny’ you came by!’ ” White remembered. “I said, ‘Thank you, ma’am!’ ”

Though White kept missing Malone when he stopped by the house, he always stayed around to spend time with Mary Malone. When they finally met, Malone and White clicked, mainly based on how much Mary Malone had talked about this guy H.

White successfully landed Malone’s commitment to Maryland, which the star center ultimately reneged upon a week before the start of his freshman year. Malone once showed White a note he wrote to himself as a young teenager. Malone had penned his goal to become the first basketball player to turn pro straight out of high school on a piece of paper he kept tucked in his Bible. Of course, the prospect of caring for his mother so she didn’t have to work so hard anymore motivated him most. And White understood.

In 1974, the Utah Stars of the American Basketball Association selected Malone in the third round of the league’s draft. Without hesitation, White drove to Petersburg and gave the 19-year-old Moses his blessing to sign the multi-year contract, worth up to $3 million, to turn pro.

“I told Mo,” White recalled, “ ‘You — and we — ain’t gonna break no promises to God.’ ”

The Houston Rockets selected Lucas — the point guard who replaced White as a starter during White’s senior year at Maryland — with the No. 1 overall pick in the 1976 NBA draft.

Over the years, White remained in touch with Lucas, who had a sister named Cheryl. White had even once met Cheryl’s boyfriend, who was introduced to him as “Kenny White” — at least by its phonetic pronunciation.

So, while plotting a career change after leaving Maryland’s coaching staff in 1978, White embarked on a relentless hunt deep in the Yellow Pages.

“There was a K-h-e-n-i White,” he recounted, the pitch of his voice seesawing. “I said, ‘NOW, I bet THAT is the guy right there!’ ”

Kheni White, who was a few years younger than White, was one of Nike’s first African-American executives, worked in the company’s then-adolescent basketball department. A hungry White hoped the brother would hear him out.

“I call the number,” White remembered, “and I say, ‘Hey, you don’t know me, but my name is Howard White.’ He said, ‘Awww, yeah, yeah, yeah. I remember you.’ ” Whether it was the truth or just banter, White delivered a pitch anyway.

A few months later, White received a call back.

“When can you start work?” Kheni White asked him. Reliving the career-changing conversation 45 years later, White slowly repeated the question, still in disbelief at the offer. “When can you start work?”

This is the origin story of the career White talked his way into and has since made entirely his own.

Two years before the company went public in 1980, Nike hired Howard White as a field marketing representative covering the East Coast. His job responsibilities were to sell the Nike dream to elite college basketball players, as Lucas had become, and provide daily support to active NBA players with Nike contracts, like Malone, then a star for the Houston Rockets after he made the jump from the ABA to the NBA in 1976.

“Here I am all of a sudden at Nike,” White said, “And the first person I get to work with? Moses.”

In preparation for Nike hosting the Jordan family in 1984, White researched the then-21-year-old Michael Jordan, who’s 13 years his junior.

“Tell me about this Michael Jordan guy. What’s your real opinion of him? Good guy? Bad guy?” White recalled asking around. “See, because those questions were far more important to me than knowing whether he could put a ball in a basket.”

Everyone in basketball, Beaverton, and the entire footwear industry knew Jordan was already set on signing with Adidas.

But Deloris Jordan, as detailed in the 1991 book Swoosh: The Unauthorized Story of Nike And The Men Who Played There, told her son he better be right next to her and his father, James R. Jordan Sr., on the plane to Oregon from North Carolina.

Before the meeting, White reached a consensus conclusion on the player Nike had its sight on.

“Michael is your kind of guy,’” White was told. “ ‘You’ll love him.’ ”

Meanwhile, Deloris Jordan, a customer service rep at a bank in her family’s hometown of Wilmington, North Carolina, had been preparing for the Nike presentation herself. Ahead of the 1984 NBA draft, she ran point in all her son’s business meetings. She notably steered the process of selecting the sports agency that would represent Jordan. The Jordan family went with ProServ and a young agent named David Falk. During the firm’s presentation to the Jordans, Deloris Jordan “liked the fact that a nice young Black attorney named Bill Strickland was part of their team,” according to The Unauthorized Story of Nike.

On the day of Nike’s pitch in Beaverton, Deloris Jordan met another young Black man who impressed her: 34-year-old White. The only thing is, when the meeting first began, White hadn’t shown up yet.

“One of the attorneys at Nike was like, ‘Let’s go get some lunch,’ ” White said. “I said, ‘Man, I got this big meeting coming up.’ He said, ‘I’m gonna take you to Helvetia Tavern, where they have one of the biggest hamburgers you’ve ever seen. Don’t worry; we’ll be back!’

“Needless to say, we did not get back in time,” White said. “MJ and his family were already there. I’m sure they said, ‘Lord, have mercy. He’s late.’ ”

To this day, Michael Jordan has jokingly never let White forget he was late. Yet back in that first meeting, a young Michael didn’t speak much. Jordan’s parents were the ones who made an initial impression on White. That day in the presentation, Deloris and James Jordan were informed that — if their son decided to sign with Nike — White would be the primary person looking out for him while he adjusted to life as a pro.

“Seeing the spirit of MJ’s parents, and feeling what they wanted for their son — therein was the bond that I built with MJ,” White said. “Therein was the thought I can believe in this young man.”

On Oct. 26, 1984, the day of his regular-season NBA debut with the Bulls, Jordan signed a five-year endorsement deal with Nike. According to The Unauthorized Story, Nike Basketball’s brain trust assigned White to lead what the company originally called the “Jordan Desk.”

White and Jordan talked daily during Jordan’s 13 seasons with the Chicago Bulls — through 14 signature sneakers, six championships, two retirements and even the tragic murder of his father. White constantly had Jordan’s ear. And if someone at Nike wanted to speak to Jordan, that person had to go through White — or “Michael’s guy,” in Nike parlance.

By the late 1980s, a rapidly rising footwear designer named Tinker Hatfield learned the chain of communication between White and Jordan the hard way.

“Originally, I didn’t even know who Tinker was,” recalled White, detailing perhaps the most pivotal period in Nike history, at least regarding Jordan. Strasser, the company’s longtime marketing director, and Moore, the designer behind the Air Jordan 1 and 2, had left to work for Adidas. Rumblings swirled that they’d eventually be joined at Adidas by Jordan, who could’ve left Nike after the third year of the partnership due to an opt-out clause in his contract. Neither Jordan nor consumers cared much for the Air Jordan 2, especially compared with the Air Jordan 1, which raked in $126 million worth of sales in the shoe’s first year on the market.

“Howard filled me in on how Nike operated,” Jordan told USA Today later. “He advised me to have input on the design of my shoe and to make the company more aware of how I felt about things.”

Essentially, Nike needed to deliver on Jordan’s third signature sneaker. And the weight of that responsibility, on an expedited timeline, fell upon a 25-year-old Hatfield, initially hired by Nike as a campus architect.

“I remember that first meeting Tinker presented to Michael,” White said. “We’re sitting there and Michael goes, ‘H, what do you think?’ I said, ‘Ehhh, it don’t look that great to me. It needs some work.’ ”

As expected, White’s comments rubbed Hatfield the wrong way. A member of Nike’s marketing department suggested that he reach out and apologize to Hatfield. So, White called. But he didn’t necessarily say he was sorry.

“ ‘We go through a lot to put together these presentations, just for you to be so dismissive,’ ” White recalled Hatfield telling him.

White’s response: “Michael asked me a question. Would you rather me lie to him or be honest? My opinion probably doesn’t matter — but he asked me.”

Hatfield retorted, whether sarcastic or genuine, “Well, do you think I should start meeting with you?”

Unintentionally, Hatfeld’s question sparked a thought in White’s head: Why not have Tinker embed with Jordan? That strategy had helped White build a strong rapport with the young star during the first few years of his Nike partnership. White ran the idea by Jordan, who signed off. Along with White, Hatfield flew to Chicago to shadow His Airness. And with the clock ticking, Hatfield locked in on the design of Jordan’s next signature sneaker.

“Tinker started to meet with Michael,” White said, “He’d come to Michael’s home, look in his closet, look in his garage, see things, be a part of it — and build shoes from it all.”

It’s no hyperbole to assert that the first shoe Hatfield designed for Jordan is why he stayed with Nike. The Air Jordan 3, adorned with rich tumbled leather and a unique pattern resembling elephant skin, was the beginning of what became the most-prolific relationship between an athlete and footwear designer in sneaker history. The Air Jordan 3 also notably introduced a new logo on the shoe’s tongue, dubbed “The Jumpman.”

By the early 1990s, Jordan had led the Bulls to a championship-contending level with Hatfield’s designs on his feet. Yet, White still remembers Jordan nearly playing the NBA Finals game in Nike running shoes.

In Game 3 of the 1991 NBA Finals between the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers, Jordan landed awkwardly on his foot while connecting on a game-tying jumper with 3.4 seconds left in regulation. Chicago won 104-96 in overtime, but Jordan had severely bruised his right big toe, which forced him to miss the Saturday practice before Sunday’s Game 4.

Jordan didn’t want to sit out, so he asked White to get two new pairs of sneakers to Los Angeles in less than 48 hours. He asked for a bigger size of the Air Jordan 6s he’d worn all playoffs and a pair of Nike Terra T/Cs — a low-top, lightweight running shoe released eight years earlier in 1983 before MJ even signed with Nike. Of course, Jordan’s sports marketing rep delivered. And White recalled that ahead of Game 4, Jordan originally left his Air Jordans at his locker.

“MJ took out the Terra T/Cs and said, ‘I’ll be able to play in them,’ ” White remembered. “He went out to warm up, and I said, ‘Well?’

“He responded: ‘Not enough support.’ ”

So, Jordan laced up the larger Air Jordan 6s — he cut a small slit in on the right toebox for relief during the game. That night, he scored 28 points, on 55% shooting from the field, with 13 assists and 5 rebounds. He led Chicago to a 97-82 win that gave the Bulls a commanding 3-1 Finals series lead.

“When he first put the 6s on, he said they hurt like the devil. By, by the second half, he was OK,” White recalled. “I wasn’t quite sure if the foot was OK or his mental was OK. Regardless, it was an amazing feat.”

The Bulls closed the series with a 108-101 win over the Lakers in Game 5 to clinch the franchise’s first NBA title. White placed two phone calls from the telephone mounted on the wall in the celebratory visitors’ locker room at The Forum. One was to Hathaway, the high school coach who taught him basketball, and another to Knight, his boss at Nike.

“I called Mr. Knight to go over the moment with him,” White said. “Just to make sure, ‘Hey, it’s like you being here. I’ll tell you everything that happened.’ ”

The most infamous conversation between White and Knight has been detailed on two notable occasions.

First, in a 1998 story in The Baltimore Sun, profiling the former University of Maryland star point guard-turned-assistant coach-turned Nike executive.

“I was supposed to be a secret agent — a spy — for Adidas,” White joked to The Sun.

In his book Believe to Achieve, White more seriously revisited the day Knight called him into his office and began asking questions about his relationship and specific telephone conversations he had with a particular former Nike employee (whose name White doesn’t disclose in the book).

“There will be times that test everything you believe in,” wrote White, recounting his tense sitdown with the Nike CEO in the early 1990s. By then, Strasser, Moore and Vaccaro had all moved on to Adidas, Nike’s biggest rival. That meant, out of all the executives who spoke in the 1984 Nike pitch to Jordan and his parents, only White and Knight remained in Beaverton.

Knight had grown wary — perhaps, even paranoid — about possible collusion between White, Jordan and former Nike employees. Ultimately, the FBI reportedly investigated the situation. After openly pleading his innocence and loyalty to Knight and Nike, White took a leave of absence.

“During that FBI investigation, he never really got upset or angry,” White’s wife Donna told The Baltimore Sun in 1998. “All he did was talk with people, venting. And, when it was over, he forgave people.”

After the FBI reportedly found no evidence of White participating in anything illegal, Knight remorsefully gave his longtime employee and friend a chance to accept an honorable discharge.

“‘If you don’t want to be here anymore, you’ll get the biggest settlement in the history of mankind,’ ” Knight told White, as recalled in the 1998 story in The Sun.

White, though, didn’t take Knight’s out: “I told him, ‘You asked me to come do a job here, and the job’s not done.’ ”

White wanted to see through a longtime goal of establishing the Air Jordan signature line as an official brand. But that unfinished job arrived at a crossroads during Jordan’s first retirement from the NBA from October 1993 to March 1995.

The question became if and when Jordan left basketball for good, how could Nike continue to design, produce, market and sell performance sneakers and apparel without Air Jordan himself. According to White, that’s the mindset Knight and even Jordan held. The boss and His Airness both openly conceded to H that the Air Jordan run, though an incredible one, would eventually end.

So, sometime in the mid-1990s, Knight and White shared another serious conversation. The following exchange might be the best story from White’s entire career at Nike.

“Let’s go back over how we do this, just in case you might’ve forgotten,” White remembered Knight telling him.

“We find a player,” Knight continued, “We build shoes for that player. Then, that player wears the shoes on the court or field. And we — Nike — sell the shoes.”

Knight then asked White how the company’s tried-and-true formula failed to align with Jordan’s looming first and presumed final NBA retirement.

“I said, ‘Well, some people will say the Jordan thing won’t work anymore if MJ’s not playing,’ ” White said.

Bingo — Knight’s exact point. Yet White disagreed. He just had to find a way to paint an alternate picture for his boss.

“I told Mr. Knight,” White recounted. “ ‘You know what’s funny? I happened to be walking in front of the Nike campus, just the other day. A Mercedes-Benz pulled up, stopped at the light, and when the light turned green, it took off!’ ”

Knight, completely confused by the rant, asked White for a clearer explanation.

“I said, ‘HOW in the WORLD did that Mercedes-Benz take off from the light?’ ” White said, playing with the pitch of his voice. “‘It really did trouble me. Because, I figure Mr. Mercedes been dead an awful, long time. So, HOW is THAT even possible!?!’ ”

Translation: In White’s mind, a brand as iconic and globally revered as Mercedes-Benz or Air Jordan didn’t need its founder, namesake or driving inspiration physically present to continue its business legacy. At the end of the rant, the Nike CEO was persuaded.

“Point well taken,” Knight told him.

By early September 1997, a month before Jordan’s final season with the Bulls, Nike launched the Jordan Brand. The sportswear company celebrated the establishment of the business with a special event at the Niketown store in New York City.

Gene Siskel, a film critic who formerly wrote for The Chicago Tribune, was assigned to cover the invite-only launch for the CBS Morning News. On Jordan’s first official day as sneaker CEO, Siskel interviewed him one-on-one. According to a published transcript, Siskel broke the ice by chatting with Jordan in the first few questions. True to his background, the film critic asked Jordan: What’s your all-time favorite comedy movie?

“Friday,” said Jordan without hesitation.

“Thank God It’s Friday, the musical?” a confused Siskel responded.

“No, Friday,” Jordan fired back to Siskel, who admitted he hadn’t seen it. “What type of a critic are you?” Jordan asked. “It was a great movie.”

Jordan loved the 1995 ’hood classic starring rapper Ice Cube and a young actor named Chris Tucker, who possessed a high-pitched voice. Jordan had been listening to one that sounded very similar for years.

Over time, texting became the preferred daily communication method. So, in late 2022, White knew something had to be wrong when Jordan’s name popped up on his phone.

He answered to a wrathful chorus sung by a worried Jordan.

“Boy, was MJ upset,” White recounted.

White had gone into the hospital for a routine procedure. Yet when Jordan heard through the grapevine about his longtime confidant’s visit to a cardiologist, he immediately dialed.

“I said, ‘It’s not that —,” White attempted to explain before Jordan cut him off. “ ‘No. You are a big deal!’ ” White said Jordan told him. “He said, ‘Man, if something happened to you, I don’t know what I’d do.’ ”

White’s cardiologist diagnosed him with congestive heart failure not long after the conversation. This time, he called Jordan to tell him that on Dec. 28, 2020, he would undergo a heart transplant. After successful surgery, White’s daughter Mandy moved back home to Lake Oswego from Texas to help her mother care for her father.

“The transplant really took a toll on him,” Mandy White said. “His quality of life just wasn’t great.”

The already-slim White began to look more frail and moved less like his typical lively self. His daily attire also shifted to Air Jordan tracksuits, while his dress shirts and ties remained in the closet.

Yet, the most challenging part of White’s recovery was learning to breathe again. As part of his recovery, he had to remain on a breathing machine for several hours as a routine precaution.

While he recovered, Mandy took on the main responsibility of keeping her father’s favorite people, such as Jordan and Barkley, in the loop on his health. One day, Jordan told her point-blank: “I need to talk to him.” Father Time had dealt White into a poker game that Jordan certainly wasn’t ready to see him lose yet. However, she assured Jordan that her dad would answer if he called. So, Jordan reached out to White on a three-way call with Hall of Fame New York Yankees shortstop Derek Jeter, who, in 1999, became the first MLB player to join the Jordan Brand. Jeter, the only baseball player to receive a signature Jordan line for the baseball diamond, is also a big White guy.

“We all talked,” White remembered, “and MJ said, ‘All right, I’m satisfied. I just needed to hear you for myself.’ ”

Slowly but surely, White began making calls on his own again. He even requested to speak to the mother of his heart donor. And, of course, he told her about his mother Lillian.

“When my moms said, ‘Even a dog can wag its tail when it passes you on the street,’ I really did take that to heart,” White said. “And now I do it for the gentle giant’s heart that’s inside of me. I told his mother that a phoenix rises from ashes. And I need to be that phoenix for her son.”

Coincidentally, Tucker said he’d given White a call every year, no matter what, ever since they met in the early 2000s at Jordan’s annual golf tournament in the Bahamas. So, when Tucker’s agents shared that Affleck wanted him to play a guy named Howard White in an Air Jordan movie, Tucker immediately blurted, “Well, wait a minute. I know Howard!”

Tucker immediately picked up the phone. But, it wasn’t until many conversations later that the actor learned about the longtime Nike executive’s heart transplant.

“Thank God he’s still here,” Tucker said. “If he wouldn’t have been here, I probably wouldn’t have done the movie. But Howard really made it worth it.”

White didn’t only personally give Tucker stories from his life and career — he also shared his overflowing Rolodex. White put “Tuck,” as he calls him, in touch with friends from his childhood in Hampton, professors he learned from at Maryland, and athletes he’s advised at Nike. “ ‘Man, Howard is like Confucius! The greatest guy in the world,’ ” Barkley told Tucker.

Inspired by countless conversations with White, and everyone around him, Tucker penned each one of his scenes as the young executive for Air. While the movie was filmed in 2022, White returned to work for the first time, two years after the heart transplant.

Dressed in a gray-pinstriped suit, with a blue-tinted tie and white pocket square, White filmed a commercial the Jordan Brand released to announce its signing of Orlando Magic rookie Paolo Banchero, the No. 1 overall pick in the 2022 NBA draft. White and Paolo sat across from each other in a booth at Helvetia Tavern, the same restaurant where a young White went to get the hamburger that made him late to the Jordan pitch in 1984.

Nearly 40 years later, the question of retirement comes up often, especially now with a movie immortalizing the beginning of his journey with Air Jordan.

Though White said he’s given it some thought, he said he’s not quite ready to retire yet.

“I don’t ever want H to ride off into the sunset, go to the house and chill,” said Saunders, who’s habitually called White daily on his way to and from work. Saunders’ children, though, might love White more than he does. His oldest son, a University of Oregon football player, had a picture of White as the screensaver on his phone for a long time. Saunders’ middle son, who has portraits of civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. and baseball pioneer Jackie Robinson tattooed on him, has teased the idea of adding one of White to his ink collection.

“When my kids come into the building, they don’t come to my office,” Saunders said. “They go straight to H’s.”

White has returned to his office in the Michael Jordan Building, which overlooks the lake in the heart of Nike’s campus. His door is back open to anyone wanting to stop by and talk. And whenever it rings, or if he just wants to catch up with a character from one of his famous stories, White will pick up the phone.

“As long as I have the ability to help somebody believe in something,” he said, “I’ll be at Jordan.”